Post 1

Message in our Music by The O’Jays

By Brett Hammerman

Music has power. The accessibility of it, as well as its longstanding cultural presence both within America and beyond its borders, allow it to drive social change. In their 1976 hit song “Message in our Music,” The O'Jays sing:

“Cause we gonna talk about all the things

That’s been goin’ down…

We got a message in our music

There’s a message in our song

So understand while you dance”

Music’s ability to carry messages gives music inherent power. The O’Jays use music to reflect on current events -- or what has “been goin’ down” -- through their music. Their song compels you to reflect on the state of our world, singing: “Things ain’t like they’re supposed to be.” The O’Jays call out broad societal issues to raise awareness and spark activism. Music, per the lyrics in their song, is their mode of “communication.” However, the O’Jays communicate a message in style, making listeners dance as the lyrics sink in; they speak to the transcendence of hearing songs. They move you (both physically and emotionally) but concurrently force you to think critically about complex issues. More than 40 years later, as our nation still wrestles with the impact of racism and the fight for Black Lives, the O’Jays song forecasts the ways music will continue to bring awareness to not just racism, but other social issues. The resonance of the song today points not only to the issues America must solve, but also speaks to music’s enduring ability to stay relevant to current discourse as a timeless capstone of our national memory.

As an artist myself, I’m struck by the song’s ability to bluntly and concisely articulate the purpose of a song. Songwriters use their talent to draw attention to key social issues that have been disregarded and left out of our collective national or global consciousness. But they also meaningfully interact with individual stories and experiences. I was clearly not alive in 1976, but that the O’Jays song can resonate so powerfully says volumes about its translatability beyond any singular moment. Often, we don’t overanalyze or unpack the lyrics of the songs that we consume. But, maybe we should. There are thousands of artists around their worlds with stories to tell, and as a society, we should begin to hear them, and we can do this by disseminating the message in their music.

By Brett Hammerman

Music has power. The accessibility of it, as well as its longstanding cultural presence both within America and beyond its borders, allow it to drive social change. In their 1976 hit song “Message in our Music,” The O'Jays sing:

“Cause we gonna talk about all the things

That’s been goin’ down…

We got a message in our music

There’s a message in our song

So understand while you dance”

Music’s ability to carry messages gives music inherent power. The O’Jays use music to reflect on current events -- or what has “been goin’ down” -- through their music. Their song compels you to reflect on the state of our world, singing: “Things ain’t like they’re supposed to be.” The O’Jays call out broad societal issues to raise awareness and spark activism. Music, per the lyrics in their song, is their mode of “communication.” However, the O’Jays communicate a message in style, making listeners dance as the lyrics sink in; they speak to the transcendence of hearing songs. They move you (both physically and emotionally) but concurrently force you to think critically about complex issues. More than 40 years later, as our nation still wrestles with the impact of racism and the fight for Black Lives, the O’Jays song forecasts the ways music will continue to bring awareness to not just racism, but other social issues. The resonance of the song today points not only to the issues America must solve, but also speaks to music’s enduring ability to stay relevant to current discourse as a timeless capstone of our national memory.

As an artist myself, I’m struck by the song’s ability to bluntly and concisely articulate the purpose of a song. Songwriters use their talent to draw attention to key social issues that have been disregarded and left out of our collective national or global consciousness. But they also meaningfully interact with individual stories and experiences. I was clearly not alive in 1976, but that the O’Jays song can resonate so powerfully says volumes about its translatability beyond any singular moment. Often, we don’t overanalyze or unpack the lyrics of the songs that we consume. But, maybe we should. There are thousands of artists around their worlds with stories to tell, and as a society, we should begin to hear them, and we can do this by disseminating the message in their music.

Post 11

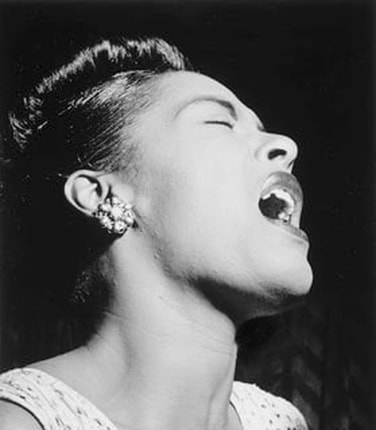

Strange Fruit by Billie Holiday

By Brett Hammerman

I get chills whenever I hear the first chord of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruits.” It’s ominous key -- B-flat minor, to be exact -- and her emotive voice commands the listener's attention. The song, released in 1939, was written to protest the lynching of black men in the South. She cries out: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze” in the very first verse. Immediately, the lyrics depict the horrifying, bloody scene of a lynching. The songs lyrics were inspired by a real case of lyhnching in the South, where images literally depicted “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.” The shocking image paired with the “Strange Fruit'' lyrics tell listeners a story of the most heinous racist act, sparing no details, no matter how gruesome.

An essay or a speech couldn’t evoke the same sense of devastation, anger, and frustration as Holiday’s song. To begin with, the melancholy, long-lasting introduction sets the tone for the lyrics to come. Additionally, the long pauses between Holiday’s singing allow the listener to consider the words Holiday had just sung. The lyrics paint a raw image of the event that gave rise to the song, and listeners can begin to “see” what happened through each lyric -- like a puzzle, each line adds a new component to the picture, from the picturesque “Pastoral scene of the gallant South” to the contrasting “smell of burning flesh.” Furthermore, her constantly changing melodies and powerful vocals alone alarm listeners to hear and process the lyrics.

Nowadays, the song is celebrated as a strong, timeless protest song. However, when it was first released, the song made Holiday a “go-to” target for racist acts, and at times she even feared her safety while performing it. She risked her own security in order to send a message to the world that lynchings must stop and that we all must act to dismantle racism in society. In this sense, Holiday is a perfect example of an artist using their voice and platform to raise awareness of inequalities and call listeners to action. When a person hears “Strange Fruit” today, one might connect the song’s topic -- the lynchings of Holiday’s time -- to the systemic racism we see today, and the continual murder of black Americans. The song protests injustice, and we can return to this song to continue to protest the status quo.

By Brett Hammerman

I get chills whenever I hear the first chord of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruits.” It’s ominous key -- B-flat minor, to be exact -- and her emotive voice commands the listener's attention. The song, released in 1939, was written to protest the lynching of black men in the South. She cries out: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze” in the very first verse. Immediately, the lyrics depict the horrifying, bloody scene of a lynching. The songs lyrics were inspired by a real case of lyhnching in the South, where images literally depicted “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.” The shocking image paired with the “Strange Fruit'' lyrics tell listeners a story of the most heinous racist act, sparing no details, no matter how gruesome.

An essay or a speech couldn’t evoke the same sense of devastation, anger, and frustration as Holiday’s song. To begin with, the melancholy, long-lasting introduction sets the tone for the lyrics to come. Additionally, the long pauses between Holiday’s singing allow the listener to consider the words Holiday had just sung. The lyrics paint a raw image of the event that gave rise to the song, and listeners can begin to “see” what happened through each lyric -- like a puzzle, each line adds a new component to the picture, from the picturesque “Pastoral scene of the gallant South” to the contrasting “smell of burning flesh.” Furthermore, her constantly changing melodies and powerful vocals alone alarm listeners to hear and process the lyrics.

Nowadays, the song is celebrated as a strong, timeless protest song. However, when it was first released, the song made Holiday a “go-to” target for racist acts, and at times she even feared her safety while performing it. She risked her own security in order to send a message to the world that lynchings must stop and that we all must act to dismantle racism in society. In this sense, Holiday is a perfect example of an artist using their voice and platform to raise awareness of inequalities and call listeners to action. When a person hears “Strange Fruit” today, one might connect the song’s topic -- the lynchings of Holiday’s time -- to the systemic racism we see today, and the continual murder of black Americans. The song protests injustice, and we can return to this song to continue to protest the status quo.

Post 111

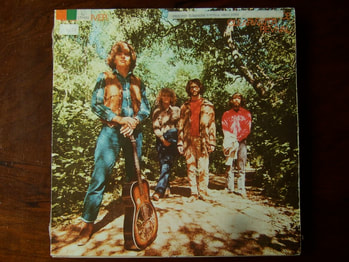

Fortunate Son by Creedence Clearwater Revival

By Brett Hammerman

In September 1969, right at the peak of the Vietnam War, Creedence Clearwater Revival released his single “Fortunate Son.” In the song, he sings about the inequity of wartime. To be a “fortunate son,” is to be related to someone with great status. “I ain’t no senator’s son,” or, “I ain’t no millionaire’s son,” he explains. During the Vietnam War, many wealthy young Americans dodged the draft because of their connections, which the others -- less “fortunate” -- were binded by law to go to war for a controversial cause. The song’s genius stems from the fact that it uses the Vietnam War as a gateway to critiquing America’s social hierarchy. Why is that “folks [that] are born silver spoon in hand” don’t have to go to war? Isn’t everyone equal? These rhetorical questions guide the listener through the 2 minute song, and perhaps, continue to plague their minds after.

The song's popularity demonstrates its wide reach. If you listen to the song, you’re compelled to think about the problems in the draft system, the idea that those that have power don’t fight on the battlefield, and the larger inequalities in America. There are many ways for listeners to have taken action -- to begin with, the Vietnam War polarized American society and caused widespread protests to end the violence overseas. The song fed off of this unique historical moment, and used it to catalyse a newfound consciousness and desire to reform our systems so that when it comes to war, all are equal; we should work to construct a country devoid of “unfortunate sons.”

One interesting component to the song is its upbeat tone: it’s a true rock and roll song. A question that comes to my mind is: how can Creedence Clearwater Revival expose the flaws within our systems and raise awareness of privilege while singing a song that stripped of its lyrics would appear euphoric? Perhaps the song’s catchiness draws listeners in, gets more radio airplay, and thus more people hear the song. Or, maybe it’s just because in music, the message of the song doesn’t always need to match the tone. Hearing the words themselves is powerful enough. This relates to the O'Jays’ “Message in our Music,” where they assert that while music carries weight, you might as well dance to it!

By Brett Hammerman

In September 1969, right at the peak of the Vietnam War, Creedence Clearwater Revival released his single “Fortunate Son.” In the song, he sings about the inequity of wartime. To be a “fortunate son,” is to be related to someone with great status. “I ain’t no senator’s son,” or, “I ain’t no millionaire’s son,” he explains. During the Vietnam War, many wealthy young Americans dodged the draft because of their connections, which the others -- less “fortunate” -- were binded by law to go to war for a controversial cause. The song’s genius stems from the fact that it uses the Vietnam War as a gateway to critiquing America’s social hierarchy. Why is that “folks [that] are born silver spoon in hand” don’t have to go to war? Isn’t everyone equal? These rhetorical questions guide the listener through the 2 minute song, and perhaps, continue to plague their minds after.

The song's popularity demonstrates its wide reach. If you listen to the song, you’re compelled to think about the problems in the draft system, the idea that those that have power don’t fight on the battlefield, and the larger inequalities in America. There are many ways for listeners to have taken action -- to begin with, the Vietnam War polarized American society and caused widespread protests to end the violence overseas. The song fed off of this unique historical moment, and used it to catalyse a newfound consciousness and desire to reform our systems so that when it comes to war, all are equal; we should work to construct a country devoid of “unfortunate sons.”

One interesting component to the song is its upbeat tone: it’s a true rock and roll song. A question that comes to my mind is: how can Creedence Clearwater Revival expose the flaws within our systems and raise awareness of privilege while singing a song that stripped of its lyrics would appear euphoric? Perhaps the song’s catchiness draws listeners in, gets more radio airplay, and thus more people hear the song. Or, maybe it’s just because in music, the message of the song doesn’t always need to match the tone. Hearing the words themselves is powerful enough. This relates to the O'Jays’ “Message in our Music,” where they assert that while music carries weight, you might as well dance to it!